I have a theory. I’m still working it out, but here goes. It’s actually two related theories or perhaps simply flip-sides of the same notion. The first is that while the human mind can become enthralled with things that are large and/or vast, it often quickly short-circuits. Think of the Grand Canyon. Okay, now what?… Or consider dinosaurs and that rogue meteor that felled them. Coolio. And then?… Maybe consider the darkest depths of the Mariana Trench. Really fucking dark and many translucent creatures that don’t understand you. Or the wide stretch of the Milky Way galaxy. Got it??… As Douglas Adams put it, “Space is big!” Maybe it’s the lack of opportunity to meet other people that so alienates (the same goes for social media!). Next, try pondering the full expanse of all recorded and unrecorded time since the universe began. Jesus H Fuck! Where does it end…???

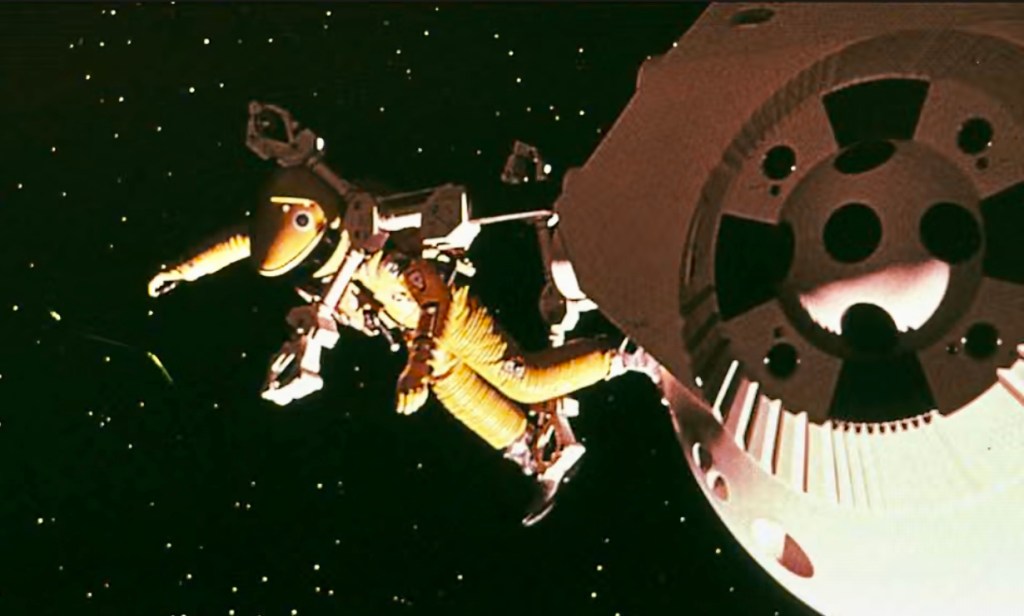

I think that for most of us, our initial fascination gets overwhelmed by a lack of detail and granularity. Unless you’re a science fiction writer, how long can you ponder the notion of distant Europa, the fourth largest moon of Jupiter? Too much to get my head around. They had to invent the concept of “hyperspace” as a mental short-cut in that genre. Contemplating a black hole might be a terrific insomnia remedy, come to think of it. The point being that even killer shit like dinosaurs are fleeting in our imagination, unless you make them more tangible. Cinema does this trick, as in “Jurassic Park,” by integrating them anachronistically into the human world. Stanley Kubrick reduced infinite space by spending much of “2001” on the ship where it was man-vs-computer (A.I.!!), first at chess and then in a fight to the death (HAL’s run ended with him pushing out “Daisy”!). One might do better if things were scaled down to the size of children’s toys — placing them in arm’s reach, allowing us to mix the dinosaur and the space ship and and the GI Joe and the Batmobile. Now you’ve got the makings of a pretty damn good STORY…

On the other hand, things rendered small and with fine detail seem to have an inordinate power over the human imagination. Questions come quickly and possibilities pour forth like a gushing pub tap carrying fanciful storylines right along with them. For example, I felt a bigger jolt from “Fantastic Voyage” than with “Interstellar.” And I would venture that Gulliver found the world of Lilliputians more intriguing by multiples than the other way round. This is also true for model train sets with their hyper-realistic signage and little carved people who wave hello and goodbye at regular intervals. These tableaus have a mystical quality that have enraptured many, including the brilliantly uncanny lyricist Neil Young, who saw Lionel trains as a way to communicate with his two severely disabled sons. The short and repeating train ride is warmly evocative in ways that depictions of space travel struggle to match. William Shatner reported back after his 11-minute space flight, saying that it filled him with an overwhelming sense of grief. Philosophers call this the “overview effect” (an existential crisis about our transience and cosmic insignificance secondary to celestial “shock and awe”), and maybe we get the opposite feeling when we scale it all down.

The Miniature Rooms at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) invite another mind journey, racing back in time and delving into the nooks and crannies of our own inventiveness. Spread across centuries of styles and countries, they evoke notions about each specific place and era, but also of the people who may have lived there and what their stories might have been. Simply put, we have questions. So, so many questions. Very detailed and site specific ones that lend themselves to story, biography, and to a shared history. I think that as humans we like to think that we think really BIG, when in fact we are much more comfortable playing small-ball. Ground level stuff. Visible and palpable (that is, not neutrino-small). As Guy Clark would say, “The stuff that works. The stuff that holds up.” Specificity and story: two of the primary nucleotide building blocks in our creative human DNA.

I’ll end it with a few good words to live by, as an exuberant Steve Martin suggested back in the day, “Let’s get SMALL!”